EMILE MALESPINE

Max and Irène Bucaille were regular visitors to Claire Fontaine, Emile Malespine’s home in the magnificent Rambouillet forest. The two men exchanged a great deal. After Emile Malespine’s death, Max and Irène Bucaille acquired the house. A place of calm and inspiration, where Max worked, painted and sculpted…

Extract from the brochure for the exhibition “MALESPINE PEINTURE INTEGRALE” Galerie Rive Gauche April 16 – May 9 1947:

“Certainly, one good painter is worth more than two lawyers, and a painting always speaks better than a preface. Instead of saying: Listen, isn’t it better to say: Look!

It’s just that, after looking, I’m always asked indiscreetly: “How do you do that?” So it becomes necessary to philosophize in the manner of a recipe.

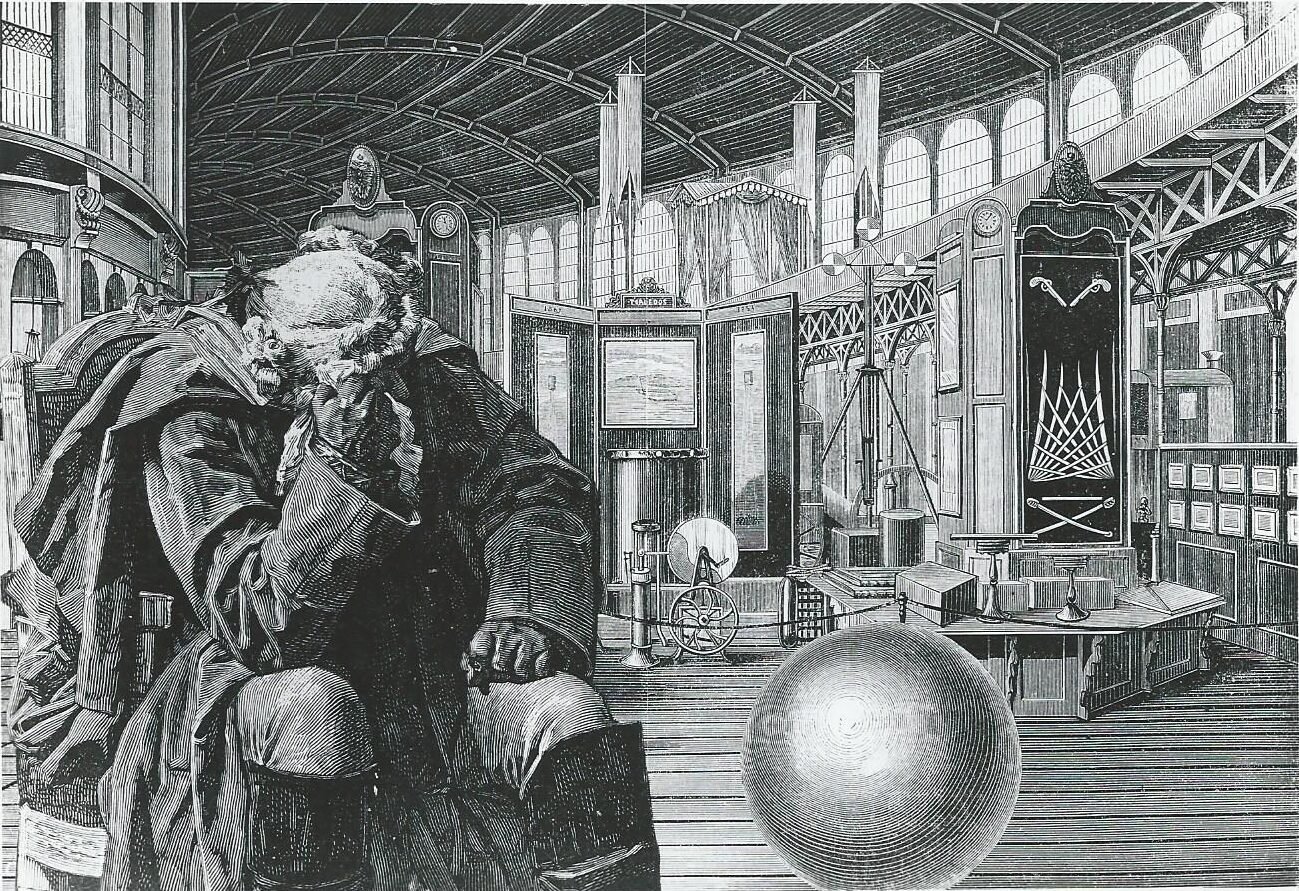

From now on, painting is where the invisible is organized. Art hijacks science and reality in favor of the imaginary and the uncertain. Apollinaire’s wish has come true: “imponderable worlds become reality”.

That’s why, without any sense of humor, I’ve been able to say: “I’m not a painter, but a painting”. In this new art, the painter is no more than a transmitter of induction. Color makes the painting. Painting that represents something has been followed by painting that represents nothing, and now by painting that represents everything.

As a rule, well-informed people oppose invention with anteriority. In fact, integralism in painting begins at the beginning of the world: in the leaf that moves, the cloud that passes, the rock that remains, the shadow that turns, there is everything, absolutely everything.

In chapter XVI of his Treatise on Painting, Leonardo da Vinci also invents the painting that represents everything: I won’t pretend to put here a new invention, or rather a way of speculating, which, although very small in appearance and almost worthy of mockery, is nevertheless very useful for awakening and opening the mind to various inventions, and here’s how: if you take heed of the dirt of some old walls or the bigarrures of some chastened stones, you may encounter inventions and representations of various landscapes, confusions of battles, witty attitudes, airs of strange heads and figures, capricious dresses and an infinite number of other things, because the mind gets excited among this confusion and discovers many inventions”.

Pictorial wholeness recreates and surpasses Vinci’s cherished “inventions”. Objective representation is reduced to its most elementary expression, and consequently to its most plastic form for the imagination. It is interpretative to the max, evocative to the max.

In the strict sense in which the physicist Niels Bohr said: “the corpuscular aspect is complementary to reality”, painting goes beyond determinism. At every moment, it flips a coin and creates a world. A few centimetres of surface area are all it takes: dreams take to the skies, singing for a moment in a rainbow, and, more impalpable than a hesitation, they sway and roll, before the imponderable cloud in turn fixes uncertain desire. As on the body of the unborn child, desire makes its indelible mark. Desire has materialized. It will be, it is becoming, it is entirely painting, reality. ”

Emile Malespine

RIVE GAUCHE GALLERY EXHIBITION “MALESPINE PEINTURE INTEGRALE” 1947.

Malespine’s work lies at the heart of invention. In the expressed forms of his science and art, a constant motive shines through: to create. His multi-faceted activity, never lingering on any one goal, radiates towards all the horizons of thought, not to acquire and merge or dissolve into them, but on the contrary, to add to them. The serene day of a good harvest matters little to Malespine. He loves the complex joy and anxiety of sowing. According to the Vedantic conception, he tends towards the consciousness of the Self, which is beyond us, and outside us, to recapture the content of the Universe.

Hence, when it came to painting, the line that Malespine defined: “Shapes, structures, colors, are but the expression of the forces that animate and direct matter, to engender these shapes, produce these structures, elaborate colors.”

The painter needed the manual means and visual possibilities capable of retaining and fixing, through form, structure and color, the expressive moment of a force. A theory would have been disappointingly gratuitous and fragile. The new tool alone was appropriate. Michaud’s current exhibition shows that Malespine has found it. The invention provides material possibilities for the renewal of painting, akin to the discovery made by the Flammands of the quattrocento, when they first ground colored earths in oil.

This pre-eminence of a technique in one of the mind’s forms of expression has lent itself to confusion. Some have called it chance. Personally, I even see in it a dangerous abandonment, a failure of the mind in the face of matter. In the initial dazzle of discovery, Malespine’s critics and friends allowed doubts to creep in. – So he gave himself over to chance, writes Georges Linze. And Michel Seuphor: – You finally agree, there is something grandiose in this nonsense, there is depth in this process…. But he adds this masterful justification: – …And, you’re stopped, looking at the painting inside yourself. This is the key word. Malespine’s paintings are viewed subjectively. You are both spectator and author, in the enchantment or drama of the painting. This university has led us to believe in a skilful and haphazard process.

– The resulting image,” wrote Jean des Vignes Rouges, ”is a mixed product of human chance and cunning combined.

Neither cunning nor chance. But creative intelligence and sensitivity. Human beings are never random. The subconscious is. The concordance between the process of the mind and its objective material extension. The intuitive grasp of the concrete fact, in the time it takes to crystallize, in reality, the object of thought. Encounters and outcomes. Not coincidences.

The most confusing and surprising thing about seeing a Malespine work for the first time is its plastic organization.

Until Malespine, the conductive line balances, as broadly as possible, and as little as possible, curves with straight lines. Beneath the broken lines of the figures and objects, the eye easily finds this very simple order. It’s an age-old certainty for the mind.

With Malespine, everything explodes. It’s been called atomic painting. The plastic balance is radiant. Stellar. If we want an approximation by example, we find Van Gogh’s sidereal painting. But a more direct affirmation of the element. A moment in the chaos where genesis is ordered. The painter wisely noted: – In integral painting, there is everything; the world come and to come? Just as there is everything on the leaf that moves, the rock that remains, the shadow that turns.

But this everything? This universe in the infinity of time? Can chance express it on canvas?

Chance would result in meaningless impasto. Malespine intervenes lucidly and skilfully, to bring out the form, structure and color of inert matter. The dominant colors are organized a priori. Visual mastery and scientific certainty take care of the rest. The craft affirms the spirit.

Interesting painting solves the previously impossible: it restores the subject in non-figurative painting; starting from color, it rediscovers the object.

The light of riprap, the stratifications of the sky, the airy flight of matter, the gushing fires of springs, the limpidity of flames: impenetrable divine causes found in Malespine’s pictorial expression. We’re on the edge of an abyss. The bite of modern acids has crystallized vapors, formed and then abolished spaces, and reduced the eternal to the yardstick of our times through the medium of color on canvas.

CH. BONTOUX-MAUREL